DU DUC DE BERRY |

| janvier | février | mars | avril | mai | juin | juillet | août | septembre | octobre | novembre | décembre |

| january | february | march | april | may | june | july | august | september | october | november | december |

Pour obtenir une image plus grande et complète, cliquez sur la réduction ci-contre.

To obtain a full size picture, click on the reduced image here.

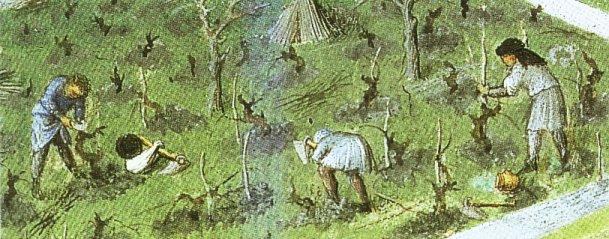

Les premiers travaux paysans de l'année. On y voit les semailles, et le labour. Ce sujet, peut-être conçu par Paul de Limbourg, et réalisé par un peintre anonyme, vers 1440, fait en quelque sorte la synthèse du monde princier et noble et dela vie paysanne.

A l'arrière-plan se dresse le château de Lusignan en Poitou, une des résidences favorites du Duc de Berry jusqu'à sa mort en 1416; il devint alors la propriété de Jean de Touraine, puis, au décès de celui-ci en mai 1417, celle du dauphin Charles, le futur Charles VII. C'est un bel exemple de château féodal du XVème siècle, dont on distingue, de droite à gauche, la Tour Poitevine d'où s'échappe la fée Mélusine, la Tour de l'Horloge,, la barbacane (ou fortification avancée) et la double enceinte. Le respect des proportions a amené certains critiques à penser que l'artiste s'est servi d'un appareil d'optique. Mais il faut surtout souligner que la précision des détails n'ôte au château rien de sa puissance et de sa position symbolique qui dominent l'enluminure.

Devant le château, on assiste aux premiers travaux des champs: le berger, aidé de son chien, garde un troupeau de moutons; plus bas, des ouvriers taillent la vigne; à droite, dans un autre enclos, une vigne déjà taillée et une maisonnette. En-dessous, un paysan se penche sur un sac, sans doute pour en prendre le grain qu'il va semer. A l'intersection des différentes pièces de terre, un petit monument, un montoire, sert de borne. Enfin, au premier plan, un paysan guide deux boeufs qui tirent une charrue.

The year's first farm work, sowing and ploughing and suchlike. This painting, probably conceptualized by Paul of Limburg, and realized by an anonymous painter, around 1440, is the right sinthesis between the Prince and the countryside life styles.

At the background, we can see the Castle Lusignan of Poitou, one of the favorite castle of the Duke of Berry untill he past away in 1416. Then, the castle has been owned by Jean de Touraine, and whe he died in may 1417,

A l'arrière-plan se dresse le château de Lusignan en Poitou, une des résidences favorites du Duc de Berry jusqu'à sa mort en 1416; il devint alors la propriété de Jean de Touraine, puis, au décès de celui-ci en mai 1417, came into the owning goods of the young Charles, future Charles VII of France. It is a good example of feodal castle of the XVth century with, from right to left, the Poteveine Tower, where the Mélusine fairy is escaping from, the Clock Tower, the barbacan (or first fortifications) and the double closed space. The right proportions of the painting let us believe that the Artist has used an optical instrument. But the main thing is problably the precision of the details of the castle, putting it as the symbol of the power and the centerpoint of the miniature.

In front of the castle, it is time for the first farm works: the shepherd, helpt by his dog, look after a mutton's drove; down, some workes are cutting the vineyard; on the right side of the picture, in closed space, an already cut vineyard and a little house. Down, a farmer is bending down over a seedsbag, probaly to take out some seeds to sow. At the crossing of two separated piece of land, we see a little headland. Finaly, at the first foreground, a farmer is leading cows, pulling a plough.

La fée Mélusine. En 1393, Jean d'Arras dédie au Duc de Berry un roman de Mélusine, que récrit vers 1401 un autre auteur, Coudrette. Selon Jean d'Arras, "il est arrivé que des fées prennent l'apparence de très belles femmes et que plusieurs en aient épousé. Elles leur avaient fait jurer de respecter certaines conditions (...) Tant qu'ils observaient ces conditions, ils jouissaient d'une situation élevée et d'une grande prospérité. Et aussitôt qu'ils manquaient à leur serment, ils perdaient leurs épouses et la chance les abandonnait peu à peu". C'est ce qui arriva à Raymondin qui, violant le pacte, découvrit le secret de la fée Mélusine, qui se métamorphosait en seprente le samedi. La fée disparut alors, et il perdit le bonheur qu'elle lui avait apporté. Les romans tendent à faire de Jean de Berry l'héritier légitime de Mélusine, fondatrice du château.

La fée Mélusine. En 1393, Jean d'Arras dédie au Duc de Berry un roman de Mélusine, que récrit vers 1401 un autre auteur, Coudrette. Selon Jean d'Arras, "il est arrivé que des fées prennent l'apparence de très belles femmes et que plusieurs en aient épousé. Elles leur avaient fait jurer de respecter certaines conditions (...) Tant qu'ils observaient ces conditions, ils jouissaient d'une situation élevée et d'une grande prospérité. Et aussitôt qu'ils manquaient à leur serment, ils perdaient leurs épouses et la chance les abandonnait peu à peu". C'est ce qui arriva à Raymondin qui, violant le pacte, découvrit le secret de la fée Mélusine, qui se métamorphosait en seprente le samedi. La fée disparut alors, et il perdit le bonheur qu'elle lui avait apporté. Les romans tendent à faire de Jean de Berry l'héritier légitime de Mélusine, fondatrice du château.

The Mélusine fairy. In 1393, Jean d'Arras wrote for the Duke of Berry a book about Mélusine, which has been rewritten by 1401 by an another author, Coudrette. According to Jean d'Arras, "It happens sometimes that fairies are shaped like very young and beautiful women. Some of the lords then get married with them. The fairies exiged from their husbands to keep the secret about their true personnality... Untill the husbands keep silent, they had a high social position and a big prosperity. But if they fail, they lose their spounces, and the chance do not lead their lives anymore". It is exactly what's happen to Raymondin, which broke his swearing, by discovering that the Mélusine fairy becomes a snake on saturday. The fairy went away, and Raymondin lost all his chance she used to bring him. The books of that time make Jean de Berry as the spritual heir of Mélusine, basemaker of the castle.

Le paysan à la charrue est un laboureur d'un certain âge qui porte une cotte bleue et un surcot (tunique) blanc. Il tient de la main droite l'aiguillon pour diriger les boeufs, et de la gauche, le mancheron de la charrue, qui s'était améliorée par l'utilisation du fer qui renforça l'action de ses pointes d'attaque, le coutre, le soc, et le versoir. L'équipe formée par l'outil, les boeufs ou les chevaux et l'homme, constituait la cellule économqiue de base. Sans doute le paysan continue-t-il à utiliser les boeufs à cause de la lourdeur de la terre.

Le paysan à la charrue est un laboureur d'un certain âge qui porte une cotte bleue et un surcot (tunique) blanc. Il tient de la main droite l'aiguillon pour diriger les boeufs, et de la gauche, le mancheron de la charrue, qui s'était améliorée par l'utilisation du fer qui renforça l'action de ses pointes d'attaque, le coutre, le soc, et le versoir. L'équipe formée par l'outil, les boeufs ou les chevaux et l'homme, constituait la cellule économqiue de base. Sans doute le paysan continue-t-il à utiliser les boeufs à cause de la lourdeur de la terre.

The man with the plough seems to be an old man with a blue dress, called a surcot. He keeps in his right hand the rope to lead the cow, and in his left one, the head of the plough, which had been improved by iron pieces, which made the plough going deeper into the earth. Thus, the three part tool ( the cow (or the horse), the plough and the man) was the basic economical unit. On this miniature, the farmer is using cows instead of horses, may be due to the tough conditions of the earth.

La vigne. Au Moyen-Age, le vignoble français était plus étendu qu'aujourd'hui, et les vins de Poitou, d'Aunis, ou de Saintonge, qui étaient surtout blancs et qui étaient exportés par La Rochelle, étaient très réputés et appréciés des Anglais et des Flamands; dans les années 1380, ce sont au moins dix mille tonneaux de vin de Poitou qu'on vendait anuuellement à Damme, avant-port de Bruges. Mais ces vins subirent la concurrence de ceux de Bordeaux dès le XIIIème siècle et de ceux de Bourgogne à la fin du XIV

La vigne. Au Moyen-Age, le vignoble français était plus étendu qu'aujourd'hui, et les vins de Poitou, d'Aunis, ou de Saintonge, qui étaient surtout blancs et qui étaient exportés par La Rochelle, étaient très réputés et appréciés des Anglais et des Flamands; dans les années 1380, ce sont au moins dix mille tonneaux de vin de Poitou qu'on vendait anuuellement à Damme, avant-port de Bruges. Mais ces vins subirent la concurrence de ceux de Bordeaux dès le XIIIème siècle et de ceux de Bourgogne à la fin du XIV

The vineyard. In Middle age, the French vineyard was larger than it is today. The white wines of Poitou, from Aunis, or Saintonge were famous around Europe, and through the port of La Rochelle, were exported. English and Flamish customers imported then more than ten thousand barrels a year in the 1380's. Most of the production was sent to Damme, port near the Belgian city of Brugges. But those wines had to face the concurrence of the wines of Bordeaux and Burgondy and the production started to decline from the XIIIth century.